- Home

- Jessica Fishman

Chutzpah & High Heels Page 5

Chutzpah & High Heels Read online

Page 5

Ester calls her contact and within a few minutes, we hear our names called out over the noise of the mob by the security guard at the front door. We feel like VIP’s again. The mob parts like the Red Sea. When we walk past the security guard, I smile when I hear him humming the tune of the Israeli song called “Jessica.”

I think back to the first time Orli and her friends sang me the song. I was at Orli’s family’s house one Saturday during my volunteer program when her friends called her to say that they would pick us up in five minutes for a picnic. That was when I feel in love with Israeli spontaneity—even though it sometimes seems like they have impulse control problems, but that’s what makes them exciting.

We quickly got ready and ran downstairs. I opened the car door and inside Liel welcomed me with an overconfident smile, but with his looks, who wouldn’t be conceited? I swooned a little before jumping in the backseat with blankets, a guitar, a mangel (grill), and a cooler. I loved hanging out with Orli’s group, speaking Hebrew, doing Israeli things, being Jewish without going to synagogue.

As we began to drive, a conversation I’d had with high-school students at my volunteer job earlier that week snuck up on me. I was supposed to be teaching them to read in English, but instead they pounced on me with questions. “How old are you?” “Do you have a boyfriend?” “Where are you from?” “Are you Jewish?”

“Of course I’m Jewish. Why else would I be here?” I had exclaimed, surprised at my defensive tone, and then quickly began speaking to them in Hebrew. I thought that if I improved my Hebrew enough, no one would ever doubt my Jewishness again.

When Liel started playing his guitar in the car, he rescued me from having to think about my fears. He started with an upbeat Israeli song and everybody else joined in.

She used to be a complete foreigner

She worked on the kibbutz for two years

But now she is somewhere else.

She said “It hurts

That nobody loves anymore”

She went somewhere else

She always thought that God

Liked to see us play music

Because that is the head of Jessica

Jessie, Jessie, Jessie, Jessi-caaaaah ooh ah ooh ah!

Ahh ooh ah ooh ah!

Now she is far away.

Orli translated the lyrics for me and told me that it was a classic Israeli song by the Ethnix from 1993, the same year as my bat mitzvah, fatefully. She said the girl in the song loved chocolate, just like me. I thought it was weird that it was such a cheerful tune, while the words seemed so depressing. I hoped the song wouldn’t jinx me.

When we arrived at the forest, we met up with a dozen other people. Within minutes it looked as if an entire army base was set up, with a full kitchen and living room. It’s no wonder how this country was built so quickly out of nothing.

At the picnic table, everyone was chatting, barbecuing, making shakshuka3, chopping salads, and smoking hookahs. I tried my hardest to understand what they were saying. Orli would turn to me after everyone laughed to explain the jokes. When I got stuck trying to say something, she knew how to finish my sentences. It felt like we had been friends since childhood.

Liel, with his contagious and irresistible laugh, was the life of the party. Every now and then he would look over at me and wink. I tried not to blush. His smile made me feel like I belonged in Israel. I felt like I was getting my first glimpse behind the curtain. I pulled Orli aside and asked her if he was single.

She smiled and said, “Ah, yes. If you like, I can make a shiduch!”

I fantasized about having an Israeli boyfriend. I imagined the romance of dating a soldier. I dreamt about having a family to go to for Friday night dinners, someone to speak Hebrew with, and a place to call home. When it started getting dark and chilly, Liel handed me his sweatshirt.

It is much colder in the Interior Ministry than it was in that forest at sunset. As Ester and I walk inside, our eyes have to quickly adjust to the darkness. We both shiver as we head up the stairwell, passing people on the steps who look like they have been waiting in the hallways for days . . . or months. Men’s stubble has begun to grow, women’s make-up is smeared, and children look like their clothing is ripping at the seams from growth spurts. Ester and I look at each other, scared to see what is upstairs as if we are in a haunted house. There isn’t supposed to be a hell in the Jewish faith, but the Israeli government sure seems to have created a perfect tenth circle for Dante’s Inferno.

We walk into a waiting room full of over two hundred people; some have set up tents and others are cooking meals on portable mangels. On the wall, we see a sign showing that they have just accepted number 37. We take the next number in the dispenser. It is number 512.

I look down at our number and wonder why the international media always makes a big deal that Palestinians have to wait at checkpoints. Why has there never been any coverage of the Israelis who wait at the Interior Ministry for days on end? Why aren’t the NGOs and the UN organizations demonstrating against this suffering?

“What are you going to do? At this pace it is going to take you a year to become Israeli,” Ester says, half-jokingly.

Instead of crying, I laugh. I wonder if the reason Jews wandered the desert for forty years is because they didn’t want to deal with Israel’s immigration bureaucracy.

Overwhelmed, I sink into the seat.

Within the next ten minutes, the number changes once and when it does, twelve different people run up to the open booth claiming to have the same number, but of course all had lost their tickets.

As I see a man trying to pick-pocket another man for his number, Ester’s connection pops around the corner with a smile . . . and a halo.

“What are you waiting here for? Come on back,” he yells, waving us back.

He whisks us away into what seems like a completely different vortex. The sun shines through the windows of the hall. There is calming music in the background. People are relaxing, drinking coffee, and gossiping.

We walk into a room with thousands of identity cards scattered like they are poker cards. I’m sure that most of the people camping in the waiting room belong to these identity cards, but won’t receive them for another few weeks.

I tense up, annoyed at the pointlessness and disorganization. I want to yell at them for hindering all of us from realizing our dreams, but am thankful that at least I’ll be getting my Israeli identity today.

“What is your name?” one of the women asks.

“Jessica Fishman,” I say, trying to do it with an Israeli accent.

“Like in the song, Jessie, Jessie, Jessie, Jessicaaaaah!” She continues singing and nods her head to the pile for us to start looking.

We dive into the pile like children searching for a toy at the bottom of a cereal box. We know better than to expect the cards to be in any sort of order, so we look at every single one.

“Here it is! I found it!” I yell and wave it in the air, feeling as if I’ve jumped over the first hurdle.

I ask if I need to sign anything or fill out any documents, but they say that it isn’t necessary. It’s comforting to know that anyone can easily steal my identity—not that I really have one in Israel yet.

As we walk out of the room, I take a closer look at my new ID. Seeing my picture with my name written in Hebrew on an official Israeli document, I almost feel reborn. I examine it to make sure they got my identity correct. I look for the line that says I’m Jewish, but I don’t see it listed4. Before I have a chance to ask, Ester reminds me that we have to rush to get everything done. I quickly stuff my ID into my pocket and push away my fear.

The Friar Society

We run out of the offices, past the people in the waiting room. Number 38 is still showing.

When we get outside, we look around and realize we don’t know where to go. I ask a random Israeli on the street, “How do we get to the Absorption Ministry?”

After he responds with the canned Israeli response for directions—�

�Go straight, straight, straight, until the end, turn right and then when you get there you’ll know”—I don’t know why I bothered asking. Last year during Yom Kippur while trying to find a synagogue, I followed these same exact directions and nearly ended up in an Arab village in East Jerusalem.

After an hour of being nomads, we decide to grab a taxi. The driver, after hearing that we wanted to go to the Absorption Ministry thought it would be best to teach us a lesson in what it really means to be Israeli and took us on a scenic route. Up until now I have been lucky and only had the nice Israeli taxi drivers. The taxi drivers who argue about five shekels one minute, but then the next minute would invite me over for a Shabbat dinner to meet their son. They would teach me Hebrew during our ride.

Just a few months ago, while I was still on the volunteer program I had an Israeli taxi driver so nice that he should have been a shaliach, ambassador. I was on my way to see Liel for the weekend. We had started seeing each other last year when Orli had played matchmaker. After hailing down a taxi, I jumped into the front seat of the cab. Israelis often times sit in front and chat with the driver; after all, the taxi drivers are Jewish too.

“Where to?” the grandfather-like driver asked me.

I gave directions to Liel’s house from Orli’s.

After hearing my accent, he curiously asked me, “Where are you from? What are you doing here?”

Since not everyone’s reaction to my aliyah was as positive as Orli and her friends’, I hesitantly told him about my volunteer program and my plans to move to Israel.

Family, friends, acquaintances, people that overheard my conversation on the bus (there is no word for eavesdropping in Hebrew since everybody’s personal affairs are considered everyone else’s business), and quite possibly the Israeli Minister of Immigration and Absorption all thought I was crazy for wanting to move here. In fact, most of them responded with the question, “Really? Why?”

Their responses were getting to me. They were making me doubt that I was making the right decision. I was getting concerned that it was going to be more difficult than I had thought. Maybe this land wouldn’t be all milk and honey.

For some reason, I desperately needed this random taxi driver to share in my excitement for Israel. Trying to figure out how to answer this taxi driver’s question without getting another negative response, I thought back to all the idealistic tales I had been told about this far, far away country while growing up. It felt like I was fulfilling a dream by moving here and I didn’t know how to sum up all these emotions in the little Hebrew I knew. So, I just said with a smile, “I’m a Zionist. I’m a Jew. Of course I want to live in Israel.”

But instead of asking me why, the driver inquisitively asked me what everyone back home thought of me moving here.

I thought about when I told most of my friends back home. They also thought I was crazy, but for a completely different reason. Most people pictured me dodging bullets on a daily basis or having to run into bomb shelters during lunch breaks. No matter how much I stated the statistics—that I was more likely to die from a car accident, a heart attack, or second-hand smoke in Israel than be killed in an exploding bus—they didn’t relax. When they asked me if I was planning on taking buses, and I responded yes, everyone became very concerned, but nobody volunteered to pay for my taxis or buy me a car.

When old my friends from high school had heard through the grapevine that I was moving to Israel, I had gotten a few emails telling me how great it was that I was going to live in the land where Jesus lived. One person had even asked me if Israel had cars yet or if they still use camels. Just for fun, I had written back, “Only the rich people have camels. Most people can only afford goats.”

“All my friends are really excited for me,” I lied.

“Well, what about your family? Won’t they miss you? What do they think?” the taxi driver asked.

Luckily, and maybe a bit surprisingly, my parents had been tremendously supportive of me wanting to move to a country where I could be killed by terrorists. But they were probably kicking themselves for sending me to synagogue, Jewish day school, on Jewish Agency missions, and for teaching me all of those Zionist values. All my parents really hoped for was to make me into a nice Jewish girl that would find and marry a nice Jewish man, a doctor or lawyer preferably, and provide them with cute Jewish grandchildren. I guess that plan backfired. Instead, I was running off to Israel, and while there were plenty of doctors and lawyers here, I had been finding out that nice Jewish guys were few and far between. “They’re happy for me, but they are going to miss me,” I finally answered, truthfully.

The driver nodded and then I told him how I was planning on joining the IDF Spokesperson Unit.

When I told Israelis my dream of serving in the IDF Spokesperson Unit, most gave me the same look that they would give a little kid who said that he wanted to be an astronaut when he grew up. Then they would rhetorically ask me, “At chai b’seret?” literally asking me if I was living in a movie. I thought this meant that I was a superhero or a superstar, until Orli told me it meant that they thought I was living in a fantasy world. I was beginning to realize that getting into the unit of my choice was not going to be easy, but I refused to give up hope.

After telling the driver about my IDF dreams, I expected to receive that same look. Instead he said, “I’m proud of you. We need more people like you in this country. You must be a very brave young woman to move here alone.”

I wanted to tell him how just the other week I had actually met an officer in the IDF Spokesperson Unit. I wanted to tell him how excited I was to sit at the IDF Spokesperson Headquarters and how I had stared at the badge the officer wore, but I didn’t, because I didn’t want to tell the driver that the officer gave me the same negative response as everyone else. Instead, I just reached over and gave the driver a hug. I was so thrilled to finally receive support for my decision that I thought I should leave him an unaccustomed tip, until I quickly came to my senses and realized that he was probably overcharging me since he had heard my American accent.

I grabbed my overnight bag and headed up to see Liel.

Now, waiting to get to the Absorption Ministry, I realize that I’m going to have to be tougher to survive. Just like I was with that taxi driver and with Liel. I miss Liel. But I had pushed Liel away to protect myself. I was afraid that if I had a boyfriend here, I’d become dependent on him, and if we broke up, then my life in Israel would collapse. I was determined not to end up like all the stereotypical American girls who move back to the US after a breakup here. I was going to be a real Israeli. I was going to have an Israeli family, not just an Israeli fling.

Ester nudges me to get out of the taxi when we arrive at the Absorption Ministry. Walking in, I realize that the Interior Ministry is methodical and technologically advanced in comparison.

“At least the Absorptions Ministry has slightly improved its absorption process since the state’s founding when they would spray new arrivals with asbestos,” I joke, trying to cheer us up.

“Who is next in line?” I ask the crowd.

Everyone gives the same response: “Me.” No one admits to being last.

A young, tiny, tan South American woman begins screaming in a high-pitched voice at a big, brawly, Russian man who is ahead of her in line. The Russian man actually looks afraid of her.

Since the Absorption Ministry deals with new immigrants from all over the world, and not with native Israelis, everyone here has different cultural backgrounds and speaks different languages. The one thing that everyone has in common is that they are fresh off the boat, barely speak Hebrew, and are eager to prove that they are just as tough as native Israelis.

The man and the woman are yelling at each other in heavily-accented and broken Hebrew. Neither of them can express exactly what they want to say, so they just yell louder and get more frustrated.

It is clear that both the woman and the man are afraid to be called a friar or “sucker.” In Israel, being a fr

iar is the worst possible fate. Being called a friar is worse than being called a liar, cheater, thief, or terrorist. Because of this most new immigrants, including myself, develop a phobia of getting screwed over. I think that this fear is in the dictionary as friaraphobia or in the medical dictionary as N.I.I.S.—New Israeli Immigrant Syndrome, which is very similar to post traumatic stress disorder.

Ester and I watch the fight, amused that neither of them can understand what the other is saying. As they get more frustrated, they both regress to yelling in their native languages. Other people join the argument, yelling in French, Spanish, English, Russian, Italian, German, and Amharic. With all of the different languages and the inability to find a solution, the room starts sounding like a UN conference, except no one seems to be sanctioning Israel.

As the fight intensifies, Ester and I sneak around everyone into one of the open offices where we are greeted by a woman sitting at her desk, drinking a cup of coffee and smoking a cigarette. Looking like she just woke up from a nap, she motions to the seats in front of her cluttered desk. Her nails look long enough to be weapons.

Ester and I sit down.

Behind the woman is a framed poster with a picture of a thorny cactus in the desert that says, “We didn’t promise a rose garden” with a stamp of the Israeli Absorption center. I don’t remember seeing this poster displayed in any of the pre-aliyah offices. The picture gives me a jolt and my fears of fitting in hit me like a physical wave. I suddenly understand why Dorthy wanted to go home so badly, despite how beautiful the Land of Oz was.

The woman taps her nails rhythmically on the desk to motion for us to start talking.

“Before a day we done aliyah. Now need our rights,” Esther tries to explain in broken Hebrew.

The woman makes it obvious that she deals with people who do not know Hebrew on a daily basis. She makes it even more obvious that she doesn’t have the patience for it. I don’t understand why someone would choose to work at an immigration ministry if they don’t like new immigrants. It would be like someone who hates children becoming a kindergarten teacher.

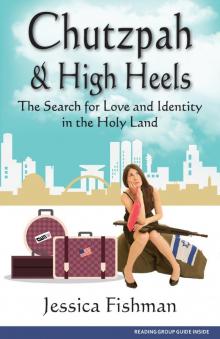

Chutzpah & High Heels

Chutzpah & High Heels